Lansing’s Universalists and the Socialist Spirit of 1915

by Ed Busch, UU Lansing Church Archivist

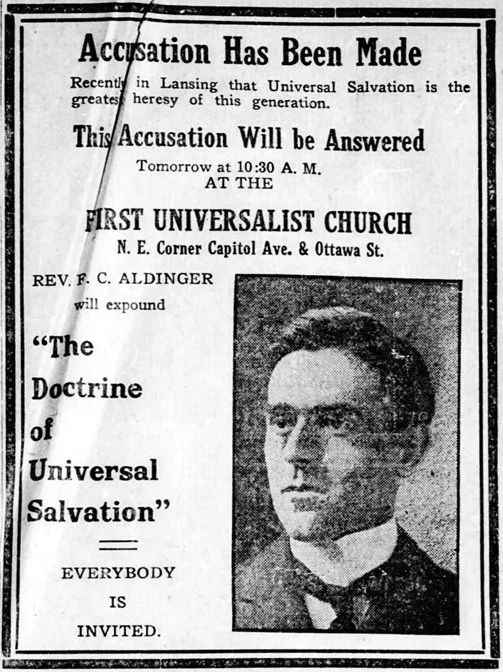

In November 1915, Lansing’s First Universalist Church at Capitol Avenue and Ottawa Street was alive with ideas—and controversy. The Lansing State Journal reported that Rev. Frederick Charles Aldinger, the church’s minister, invited “all thoughtful, open-minded people” to hear him address charges that Universalists “sneer at Jesus Christ.” His sermon, “The Christ the Universalist Church Believes In,” offered a modern, humanistic understanding of Jesus—“the Christ of history, humanity, and rational experience.” The following week, he tackled another hot topic: the supposed “heresy” of Universal Salvation.

Lansing State Journal, Nov. 6, 1915, page 4.

A Church Engaged with Its World

Throughout November 1915, the Universalist sanctuary became a forum for debate about faith, justice, and the world’s direction as the Great War raged in Europe. Rev. Aldinger hosted Rev. Edward Ellis Carr of Chicago, editor of The Christian Socialist, who delivered a three-day lecture series titled “The Mark of the Beast,” “The Reign of the Working Class Foretold in the Bible,” and “The Kingdom of God a Social State.” Carr argued that scripture itself condemned the profit system and predicted the “reign of the working class.”

November 1915 Christian Socialist newspaper (https://archive.org/details/per_atla-microtext-project_christian-socialist_1915-11_12_11)

Later that month, Emil Seidel—the former Socialist mayor of Milwaukee and 1912 vice-presidential candidate—spoke at the Universalist Church, criticizing economic inequality, Lansing’s unpaved streets, and the “preparedness” movement drawing America toward war. “Socialism,” Seidel declared, “is sweeping Lansing.”

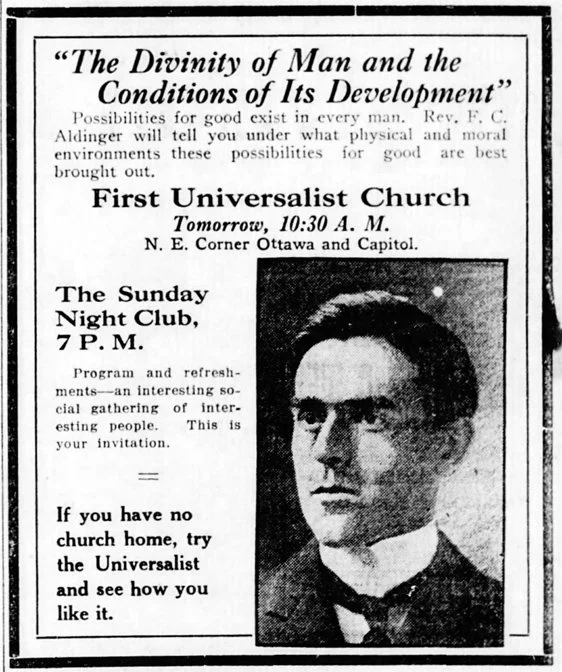

While these headline events filled the sanctuary, the church’s women sustained its life with equal vigor—hosting “thimble parties,” sewing for the Christmas fair, and serving “bohemian lunches.” Aldinger’s sermon later that month, “The Divinity of Man and the Conditions of Its Development,” reflected the Universalist conviction that human goodness could flourish under just and humane conditions.

Lansing State Journal, November 27, 1915.

Rev. Frederick Charles Aldinger (1873 – 1962)

Biographical information about Aldinger comes from Dedicated Lives: 162 Years of Liberal Ministry and Its Ministers in Lansing, Michigan 1849–2011 (2011) by Ed Busch, Shirley Beckman, and Harry Schwarzweller — available at Amazon.

Born in Frankfort, New York, Aldinger was the son of John and Sarah Evans Aldinger. He attended Buena Vista College and Drake University, earning his Bachelor of Arts in 1898, then continued at Yale and the University of Chicago, where he received his Bachelor of Divinity in 1907. After early pastorates in Iowa and Grand Rapids—where he faced charges of heresy and formed an independent congregation—he came to Lansing’s First Universalist Church, installed on February 7, 1909.

His inaugural sermon, “The True Religion,” declared:

“Every new change in the development of our civilization calls for a restatement of truth. Religion must change, make new manifestations to meet the new demands.”

Aldinger’s Sunday Open Forum attracted people from across Lansing, mirroring the free-discussion tradition that continues in our East Lansing congregation today. He remained at the Lansing church until 1918, later serving on the Lansing School Board and co-authoring The History and Growth of the Lansing Public Schools (1847–1944). Though he eventually left fellowship with the Universalist Church, Aldinger’s influence as both pastor and public intellectual remained part of Lansing’s civic and spiritual fabric.

Reflections from 2025

Looking back 110 years later, the Universalists’ activism and intellectual openness feel strikingly familiar. In 1915, amid war abroad and social unrest at home, Aldinger and his congregation welcomed debate about faith, economics, and human progress. Their sanctuary was both a pulpit and a public square.

Today, Unitarian Universalists still wrestle with the same questions—how to live our values amid social division, how to balance spirituality with justice, how to stay open-minded in a polarized world. The Lansing Universalists of 1915 remind us that these struggles are not new. They modeled a faith both compassionate and courageous—a legacy still alive in our congregation today.

We’d love to hear from you!

Do you have comments, corrections, or suggestions for future stories about our congregation’s history? Please email these atouucgl.archives@gmail.com. Your insights help keep our shared story alive. And your comments of delight for these stories are always appreciated!

[Editorial assistance provided by ChatGPT, an AI-based writing tool used to support historical documentation and clarity of presentation.]

Sources: November 1915 editions of the Lansing State Journal and Dedicated Lives: 162 Years of Liberal Ministry and Its Ministers in Lansing, Michigan 1849–2011 (Ed Busch, Shirley Beckman & Harry Schwarzweller, 2011).

About the Author

Ed Busch is a retired archivist from the Michigan State University Archives and Historical Collections and a volunteer with the UU Lansing Church Archives. He is a co-author of Dedicated Lives: 162 Years of Liberal Ministry and Its Ministers in Lansing, Michigan 1849–2011 and writes about the people and events that have shaped Unitarian Universalism in mid-Michigan.